The art of Toreutics involves creating lines and patterns on metal objects such as copper, gold, silver, and brass. Toreutics is one of the traditional arts of Iran. In the past, the creation of copper, silver, and brass objects was carried out using the cold working method, known as "Dawaatgari." The interior or underside of the objects is filled with a mixture of tar and gypsum, and by using appropriate hammers and chisels, grooves and designs are shaped onto gold, silver, or copper objects. Afterward, the tar is removed, the surface is smoothed, and the grooves are covered with charcoal and polishing oil. Then, the designs became visible as dark lines by pouring more charcoal dust over them. The art of Toreutics became common during the Achaemenids (330 to 550 BC) and reached its peak during the Sassanian era (224 to 651 AD).

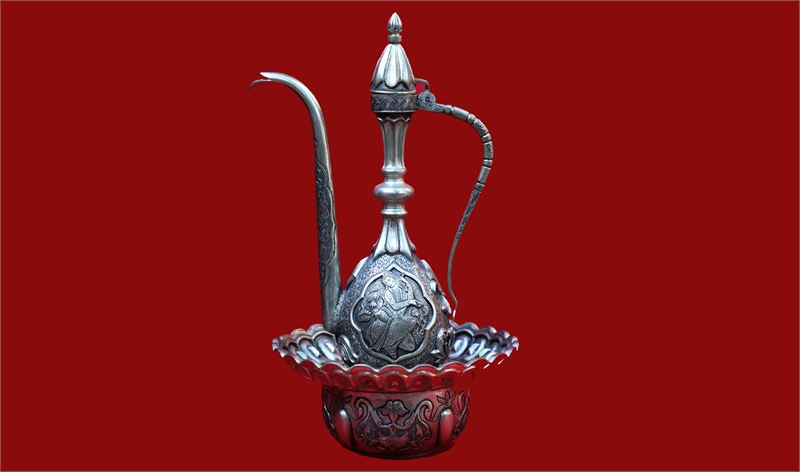

Title of the Artwork: Ewer and Basin/Material: Copper with a silver coating/Designs Used: The basin is designed with arabesque, floral, and bird motifs and the ewer is designed with floral and lily patterns/Dimensions: 22 centimeters in diameter for the basin and 43 centimeters in height, including the ewer/Engraving Technique: Semi-relief and fine engraving/Function: It was used for washing hands after eating meals

Title of the Artwork: Ewer and Basin/Material: Copper with a silver coating/Designs Used: The basin is designed with arabesque, floral, and bird motifs and the ewer is designed with floral and lily patterns/Dimensions: 22 centimeters in diameter for the basin and 43 centimeters in height, including the ewer/Engraving Technique: Semi-relief and fine engraving/Function: It was used for washing hands after eating mealsToreutics is not merely the skill of chiseling and hammering a metal object by a proficient craftsman. This art embodies human enthusiasm and creativity in employing tools, grounded in deep contemplation and reflection. It signifies an individual's profound exploration of nature and its creations, leading to an active and conscious movement in the creation of artistic works. Iran has consistently served as a cradle for the creation of pure, authentic, and spiritual arts that harmonize with the lives and customs of diverse communities and ethnic groups. The artifacts left from past eras illustrate a continuous movement that captures the tangible symbols of human life in the form of vessels, cups, and other items.

Title of the Artwork: Tray or Platter/Material: Copper with a tincoating/Designs Used: The central design of tray is lion hunting ground and edge patterns are arabesque, floral and bird motifs/Dimensions: Diameter of the tray = 70 centimeters /Engraving Technique: Fine engraving/Function: Historically used as a food serving tray

Title of the Artwork: Tray or Platter/Material: Copper with a tincoating/Designs Used: The central design of tray is lion hunting ground and edge patterns are arabesque, floral and bird motifs/Dimensions: Diameter of the tray = 70 centimeters /Engraving Technique: Fine engraving/Function: Historically used as a food serving trayThe history of Toreutics can be traced back to the Scythian era (8th century BC), and the utilization of metals, particularly copper in Iran, extends several millennia into the past. In the early first millennium and late second millennium BC, the art of metalworking flourished across various regions of Iran. Noteworthy artifacts from this period include the Marlik cup and the golden bowl of Hasanlu which are characterized by relief designs, discovered in Iran in 1957. The Achaemenid era represented the pinnacle of metalworking artistry, particularly in casting, hammering, and inlaying techniques. This art form continued to thrive during the Parthian period with the creation of statues made from gold, silver, and bronze using casting methods, as well as the production of inlaid jewelry featuring precious stones. The expansion of trade and commerce between Iran and Greece during the Sassanian period resulted in mutual influences among Greek, Roman, and Iranian arts.

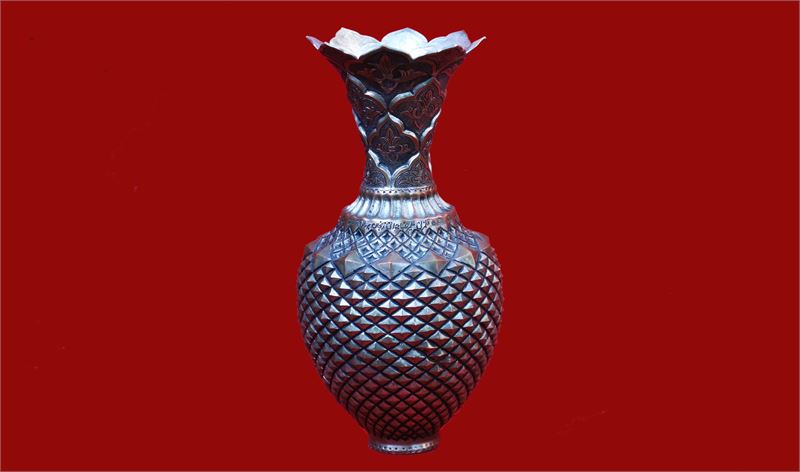

Title of the Artwork: Vase/Material: Copper with a silver coating/Designs Used: Pyramid and arabesque motifs/Dimensions: 12 centimeters in diameter and 22 centimeters in height/Engraving Technique: Semi-relief

Title of the Artwork: Vase/Material: Copper with a silver coating/Designs Used: Pyramid and arabesque motifs/Dimensions: 12 centimeters in diameter and 22 centimeters in height/Engraving Technique: Semi-reliefToreutics is executed utilizing various techniques contingent upon the shape and magnitude of the object. When patterns are created on the surface by making incisions and grooves with a chisel, it is referred to as engraving. The photographic method involves creating shadows to reveal the range of the designs. In the relief or semi-relief method, artists create a semi-relief effect by immersing the background using hammer strikes on the tool, revealing the design, which is then embellished with fine detailing. The background method involves engraving and overlaying fine and delicate patterns on the surface of metal objects, creating texture that distinguishes the design from the background. The latticework method entails excising the spaces between motifs or parts of them, permitting light to permeate, bestowing the object or plaque a lattice-like appearance.

In the early Islamic centuries, Iranian artists, influenced by Islamic beliefs, commenced the creation of metal works, gradually supplanting indigenous and mythical designs with Kufic script, verses, and hadiths. The art of Toreutics continued during the Safavid era (1501 to 1731 AD), preserving past traditions while introducing intricate and delicate motifs in place of larger, bolder designs. The gilding of metals expanded, and the incorporation of calligraphy, particularly the Nastaliq style, enhanced the beauty of these objects. During this period, the ornamentation on vessels presents significant transformations, with increasing delicacy and beauty in floral and plant motifs, as well as enhanced aesthetics in human and animal figures. In the Qajar era (1796 to 1925 AD), the production of quotidian items such as trays on copper and brass vessels featuring intertwined floral and arabesque designs, alongside motifs of animals and birds, became prevalent. The art of Toreutics has thus evolved through various historical epochs, reflecting the cultural and artistic developments of Iranian society.

Title of the Artwork: Soup Serving Dish/Material: Copper/Designs Used: The lid and its underneath is designed with pyramidal pattern, floral and bird motifs, and above the base has floral and bird patterns/Dimensions: 28 centimeters in diameter and 50 centimeters in height/Engraving Technique: Semi-relief

Title of the Artwork: Soup Serving Dish/Material: Copper/Designs Used: The lid and its underneath is designed with pyramidal pattern, floral and bird motifs, and above the base has floral and bird patterns/Dimensions: 28 centimeters in diameter and 50 centimeters in height/Engraving Technique: Semi-reliefIn contemporary Iran, the art of Toreutics endeavors to preserve traditional practices while integrating innovations to enhance the beauty of artistic creations. Through the diligent efforts of artisans, previously neglected engraving techniques have been resurrected. The revelation of artistic secrets and the aesthetic appeal of historical works, in conjunction with the engagement of designers and painters, has inspired Toreutics artists to innovate while drawing upon the creativity and insights of their forerunners. This has led to the production of unique artworks that are notable for their artistic merit. Among these artisans, Mr. Ali Javani is acknowledged as a distinguished personage in the domain of Toreutics, persistently working to preserve and transmit this intangible cultural heritage.

Mr. Alireza Javani is recognized as one of the most eminent artists in the field of Toreutics in Zanjan, Iran, who has been actively engaged in this craft for numerous years. In 2015, he achieved two national quality awards in Iran. As a prominent master of Toreutics, he has dedicated himself not only to the creation of valuable and exquisite works but also to education and transmission of the skills associated with this intangible cultural heritage to aspiring practitioners.

Mr. Alireza Javani is recognized as one of the most eminent artists in the field of Toreutics in Zanjan, Iran, who has been actively engaged in this craft for numerous years. In 2015, he achieved two national quality awards in Iran. As a prominent master of Toreutics, he has dedicated himself not only to the creation of valuable and exquisite works but also to education and transmission of the skills associated with this intangible cultural heritage to aspiring practitioners.---------------------

This article was contributed by Mr. Akbar Karimi, the international reporter for Arirang Culture Connect and the Founder and Managing Director of the Samte Ganjineye Ghoghnoos Cultural-Artistic Institute in Iran. His leadership in preserving and promoting Iranian intangible cultural heritage, along with his extensive experience in cultural-artistic research and his active participation in international forums such as UNESCO and ICCN, enriches his contributions to the global cultural dialogue.

Translated by Miss. Fereshte Abdi

Translation supervisor, Mrs. Farnaz Seydi, the director of international relations of Samte Ganjineye Ghoghnoos Institute

Photo by: Mr. Mojtaba Jafarloo